Patients get called a lot of things these days. Simon Stevens, for example, referred to them as the “renewable energy” of health services. The NHS White Paper called them “the heart” of the NHS. We at PRIMER (the Primary care Research in Manchester Engagement Resource), however, decided to call them hackers.

More specifically, we invited patients to “be” hackers—to hack into health research by pitching their own ideas for new research projects. The format was borrowed from the existing NHS Hack Days (wonderfully subtitled as “geeks who love the NHS”), which bring together tech experts, such as programmers and developers, with medical experts, doctors, and nurses to work together on new tech ideas that would improve some aspect of healthcare.

Instead, we brought together “experts by experience”—patients, carers, and members of the public—with researchers to collaborate on new research project proposals. As well as being a nod to the borrowed NHS Hack Day format, we liked the way “hacker” hints at the role of patient and public involvement (PPI) partners as the disruptive influence in research, bringing innovation and new ideas. Rather than just being invited to sit on a steering group, which is often the format for involvement, these patients were hacking their way into research, and bringing expertise and experience beyond our usual borders.

We’ve been fortunate enough in the PRIMER group to develop two research projects based on PPI partner ideas. We wanted other researchers, patients, and members of the public to be able to experience the excitement—and challenge—of working together to turn a PPI inspired idea into an actual proposal. PPI resources are typically limited though, and so we wanted to test the idea of using a brief Hack Day format to give researchers and PPI partners a space to explore new ideas and swap experience and expertise. So, on 30 April 2014, 60 participants (around 25 researchers and 35 patients, carers, volunteers, and other members of the public interested in health research) came together for four hours to see if they could build new research proposals.

Participants were given a “research toolkit” to help the teams think about how to build a research proposal.

Participants were given a “research toolkit” to help the teams think about how to build a research proposal.

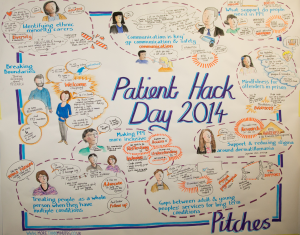

One of the main draws of the day was that PPI partners themselves were pitching the ideas. One definition of a hacker is someone who “circumvents established or protected systems,” and we think those who pitched ideas were delighted to have the opportunity to choose the research topic, rather than consulting on predefined ideas. We actually had to limit the number of pitches, and already have a waiting list of people eager to pitch at a future event. The passion and openness of the pitchers was inspiring, with ideas drawn both from personal experiences and from a heartfelt desire to help the NHS improve. I challenge anyone to look at the visual summary of the ideas and say that patients don’t have anything to bring to research.

Visual minutes of the pitch ideas by @morethanminutes.

Visual minutes of the pitch ideas by @morethanminutes.

It’s worth mentioning that the evaluation showed that 98% of attendees said they enjoyed the event. This might seem like a small thing, compared with the bigger messages of coproduction and innovation. But in our experience, PPI activities can sometimes be a fairly mundane affair—based on traditional academic ways of working—or worse a source of tension and unease. The fact that a bunch of researchers and patients can spend four hours together and enjoy it is reassuring.

Rome wasn’t built in a day of course, and neither are research projects, or long term patient and public collaborations. Sustainability after the event was a crucial consideration, and we tried to make sure people were signposted to support to help them take their ideas forward. Managing expectations was paramount: we didn’t have funds to take ideas forward ourselves, and so projects would have to look for independent funding, or integrate themselves with existing funded studies.

Getting a research project off the ground is a very difficult process, but we hope the Hack Day gave people a jump start in thinking about how their idea could move forward—and whether working with researchers was really something they wanted to do. Of the six research projects pitched, four are currently going forward in some concrete way.

We think we now have proof of principle that Patient Hack Days work. Eighty five per cent of participants said they thought the Hack Day format was effective, and 94% would attend again. We’re now looking for ways to run more events, incorporating the lessons we’ve learned.

Too often when we use the acronym PPI, people think we’re talking about mishandled insurance fraud (as those of us who struggle with #PPI on Twitter know all too well). Maybe, given the connotations of someone running off with your credit card, we should have thought twice before adding the term “hacker” into the mix. But then again, as the Hack Day demonstrated, maybe in health research we actually should be handing over the cards to the other guys that bit more often.

The Patient Hack Day was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, the University of Manchester Faculty of Medicine, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research. We would particularly like to thank Dr Bella Starling and Dr John Baker for their support.

Sarah Knowles is an NIHR School for Primary Care research fellow at the University of Manchester. Her research is focused on mental health, technology, and patient and public involvement. You can follow her on Twitter @dr_know.

Sarah Knowles is an NIHR School for Primary Care research fellow at the University of Manchester. Her research is focused on mental health, technology, and patient and public involvement. You can follow her on Twitter @dr_know.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.

Claire Planner is a research associate at the Centre for Primary Care at the University of Manchester and coordinator of the PRIMER PPI group hosted at the Centre. You can follow her on Twitter @Claireplanner.

Claire Planner is a research associate at the Centre for Primary Care at the University of Manchester and coordinator of the PRIMER PPI group hosted at the Centre. You can follow her on Twitter @Claireplanner.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.

Ailsa Donnelly is lay chair of the PRIMER group and a firm believer in active patient/carer/public/lay involvement in health research. You can follow her on Twitter @AilsaDon.

Ailsa Donnelly is lay chair of the PRIMER group and a firm believer in active patient/carer/public/lay involvement in health research. You can follow her on Twitter @AilsaDon.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.

Suzy Bourke is a founding member of the PRIMER group. She is a service user and a carer, with extensive experience in supporting patient, public, and carer involvement in clinical audit, research, and service improvement. You can follow her on Twitter @suzybee2.

Suzy Bourke is a founding member of the PRIMER group. She is a service user and a carer, with extensive experience in supporting patient, public, and carer involvement in clinical audit, research, and service improvement. You can follow her on Twitter @suzybee2.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.